What is coaching?

The International Coaching Federation defines coaching as:

partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential. The process of coaching often unlocks previously untapped sources of imagination, productivity and leadership.

ICF, nd

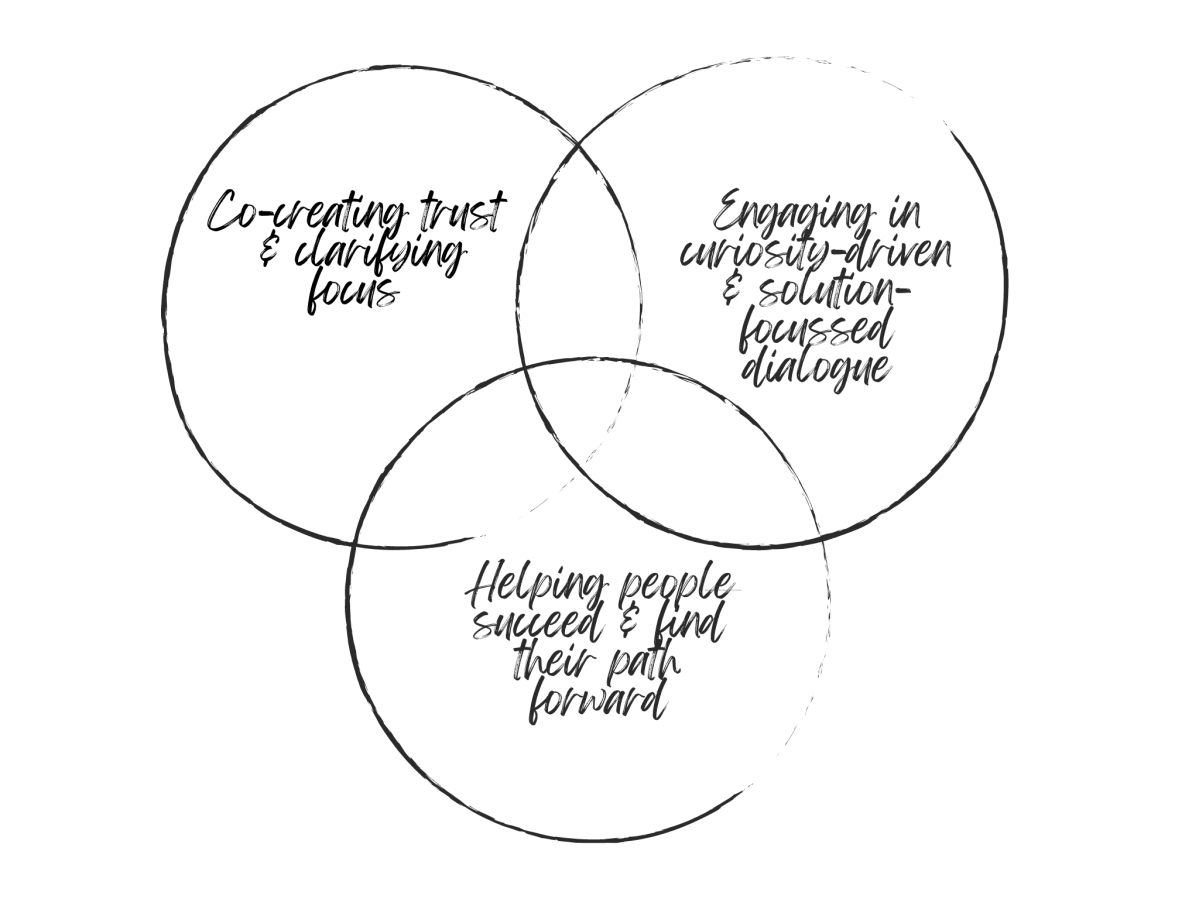

In practice, coaching involves partnering with people through an emerging process of generative self-discovery, curiosity-driven inquiry, deep listening, reframing, and future-focussed action, learning and growth (Maltbia, et al., 2014). Maltbia et al. (2014) highlight four factors that are critical to successful coaching relationships and engagements, which can be conceptualized from both the coachee’s and coach’s perspective: clarity in needs and focus, conditions for framing the situation and identifying barriers and support, commitment to determining desired outcomes and goals, and continuous improvement with a focus on iterative action and reflection. They further describe three essential coaching competencies:

- Co-creating relationships: building relationships based on trust and mutual respect. Developing awareness of and accessing one’s own coaching presence and engaging in metacognitive awareness and regulation of one’s own emotions and thinking.

- Productive dialogue: listening deeply to what is shared through people’s words and behaviours. Engaging in curiosity and learning-centred exploration and inquiry.

- Helping others succeed: exploring, expanding and (re)framing multiple perspectives and points of view. Partnering to facilitate action, learning, growth, and change.

What is the impact of coaching? What makes coaching effective?

Coaches help people dig deep to elevate their self-awareness and thinking, as well as their capacity for learning, growth, and change. Theeboom et al. (2014) confirm that coaching has a significant effect on a range of outcomes such as: improved performance, skill development, well-being, coping, work attitudes and goal-orientation. Their findings indicate that coaching is effective in improving functioning for individuals, even when coaching occurs across a small number of sessions. They point to the importance of solution-focussed coaching approaches, that encourage deep understanding, critical reflection, and transformative learning.

Deep learning approaches encourage people to question assumptions, make meaning, relate ideas, and use evidence to explore the broader implications and application of their learning (Entwistle and Tait, 1990; Trigwell and Prosser, 1991). When we engage in critical reflection, we create meaning by uncovering and challenging our assumptions, beliefs, and frames of reference (Mezirow, 1998). Transformative learning involves critical reflection and occurs when our previously held assumptions, beliefs and frames of reference shift and change to create new insights and understandings (Mezirow, 2003). Coaching is also often grounded in metacognition or learning more about and improving how we think and learn (Stanton et al., 2021). It may also include moments of mindfulness that encourage people to become aware of and notice their inner experiences so that they work to become more self-regulated and less reactive or “triggered” by their thoughts and emotions (Hülsheger et al., 2013). Like the best professional learning experiences, coaching is based on a social and constructive learning process that draws upon the coachee’s unique situation and experiences through collaborative dialogue (Webster-Wright, 2009).

I have experienced these conditions in action as a coachee, with many experienced executive coaches. They have helped me recognize that I am my greatest critic. I have tendencies towards fear-based thoughts and mind traps. I lean towards perfectionism and create excessively high standards for myself. AND, I know I am not alone in this.

I’ve worked with coaches to get below the surface and become more aware of and work through my fears – fears of failure, judgement, of not being deserving, smart enough, or good enough. These thoughts have not stopped, but through coaching, I’ve been able to develop future-focussed strategies to give them less space. I have learned to reframe my limiting beliefs (e.g. I am a failure.) to lifting beliefs (e.g., Nobody is perfect, I am committed to always learning and growing.). Coaches have helped me get there through their skilled presence, listening, awareness and questioning, “Is there a limiting belief in what you just shared that could be reframed or rethought?”

I’ve accepted that my emotions are often my greatest teacher, guiding me towards something in the moment that I need to pay attention to. Coaches have worked with me to develop skills in recognizing and acknowledging my emotions through mindful questioning, reflection, and awareness, “I feel the weight of what you just shared, where are you experiencing that in your body right now?” What is the emotion trying to teach you?”

I’ve learned to leverage my own gifts and strengths, “What strengths and expertise do you bring to this situation that may bring you grounding and stability?” I have leaned into the power of connecting to my own wisdom of experience and intuitive gifts – “What’s worked for you in the past? What does your gut tell you?”

Each coaching conversation has challenged me to find a path forward. I have become a much stronger and more mindful leader because of coaching. Coaches have helped me step back and metacognitively reflect, “What have you learned about yourself and your situation through this conversation?” They’ve pushed me towards action, “What’s one commitment that you will make this week based on what you’ve worked through today?” They’ve left me with challenging questions for further reflection, and they’ve helped me step back to celebrate my successes. In my experience, each coaching conversation is unique, evolving, sometimes a little messy and unpredictable, and deeply connected to what matters most given my current situation and context.

What does a coaching session look like?

How can these learning theories and approaches possibly come together in one coaching conversation? The truth is, there is no one coaching structure, framework or approach that works for all. Although it is certainly our aspiration, not all coaching conversations are deep, transformative, critically reflective, and mindful. Coaching is as much (or more) about our presence or who we be in the conversation, as it is about what we do. Who we be as a coach is often best framed in the context of the ICF Coaching Competencies:

- Demonstrates ethical practice

- Embodies a coaching mindset

- Establishes and maintains agreements

- Cultivates trust and safety

- Maintains coaching presence

- Listens actively

- Evokes awareness

- Facilitates client growth (ICF, nd).

One of the most widely used coaching models is the GROW model (Goals, Reality, Options, Wrap-Up). Coaches need to be both authentic and flexible to the context and needs of the person they are partnering with in conversation, rather than to any one structure or model (Grant, 2011). Developing this sense of authenticity and flexibility takes time and practice. Despite the shortcomings of coaching structures and models, I know from experience how much grounding they can provide. I learned through Essential Impact’s Excelerator CoachingTM framework (Engage, Enlighten, Empower, Excel, Evolve), which was embedded in our experiences through the Graduate Certificate in Executive Coaching at Royal Rhodes University.

A simplified structure for a coaching conversation

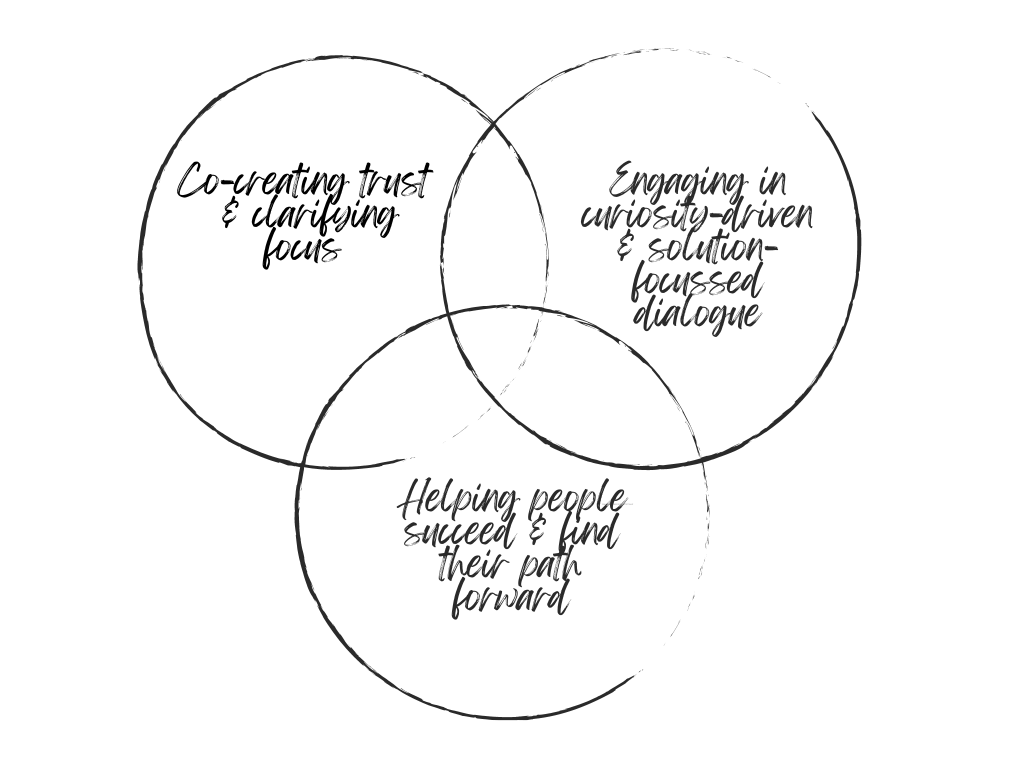

My mind gravitates towards simplification. Below I’ve adapted Maltbia et al.’s (2014) work to provide an example structure for coaching conversations based on three essential components (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Example structure for a coaching session based on three essential components: 1) co-creating trust and clarifying focus, 2) engaging in curiosity-driven and solution-focussed inquiry, 3) helping people succeed & find their path forward.

In the below section, each component is paired with guiding questions to inspire generative inquiry.

Co-creating Trust & Clarifying Focus

- What do you need to get comfortable in this space together? What do you need to transition into this conversation?

- What will be of greatest value for us to talk about today?

- What is most important about this? What’s at the core of this for you?

- What would success look like at the end of this conversation for you? What would you like to leave our conversation today with that would help you move forward?

- What would shift or change for you if you achieved this?

Engaging in Curiosity-driven & Solution-focussed Dialogue

- What do you need to work through and/or work out?

- What’s holding you back?

- What results/changes do you really want to see?

- What’s important? What matters most?

- What do you want to move towards?

- Who do you want to be as you approach this situation?

- Imagine one year down the road, you have achieved success, what does this look and feel like?

- What are you doing or not doing to support these results (or what you want to see)?

- What’s worked (or not worked) for you in the past?

- What strengths do you bring?

- What roadblocks or tensions do you experience?

- What would your wisest, kindest self say to you?

- What is yours to do? What’s your responsibility there? What do you have control or influence over?

- How might you see things differently? What else might be true?

- What are the beliefs or assumptions in what you just shared that may need to be rethought or reframed?

- In one or two words, how would you describe how you feel?

- Where do you feel that inside your body?

- What is this feeling or belief trying to teach you?

- If you could zoom out from this issue from afar, what might you notice?

- How could you put this into perspective? What is one thing you could do better?

- What advice would you give a colleague in this situation? What advice might a colleague offer to you?

- If you had nothing to lose, how might you approach this situation?

- What does your gut tell you?

- What are some possible paths forward? What other options come to mind for you? What else could you do?

- What have you heard yourself say about how you might approach this situation?

Helping People Succeed & Find their Path Forward

- Looping back to the beginning of the conversation and what you set out to accomplish, where are you now?

- What did you learn about yourself? What did you learn about your situation? How will you use this learning going forward?

- What’s shifted for you? What realizations have you had? What are your breakthroughs?

- What’s the right next step for you? What commitment (or micro-step) will you make to move forward?

- What barriers might you face?

- What resources or supports do you have to draw upon?

- How will you hold yourself accountable?

- How will you celebrate your success?

- How do we close this time together?

Despite the apparent simplicity of many coaching models and structures (including this one!), coaching is never linear. The best coaching conversations are unpredictable, dynamic, and cyclical.

Of course, it is never obvious at the start of any coaching session how the session will actually evolve, and coaches need to work with an emergent, iterative process. Indeed, for experienced coaches the uncertainty of the session and the unexpected discoveries made along the way are a large part of the joy of coaching. For the novice however, this uncertainty is often a source of anxiety and frustration and novice coaches tend to react to these feelings by to clinging too tightly to the model.

Grant (2011, p. 35)

A challenge moving forward

I encourage you to share, adapt and use this framework to help guide coaching conversations in your local context.

Try one or two questions (e.g., what’s most important? or, what else might be true?). Practice one coaching competency (e.g., listening deeply) that resonates strongly with you or that may stretch and challenge you.

The best coaches are critically reflective learners themselves. Take some time to reflect on the following:

- What worked for you?

- When did you feel most engaged?

- What barriers did you face? When did you struggle or feel challenged?

- What did you learn?

- What is one thing that you would do differently next time?

Like life, there is no perfection in coaching. It is the ultimate dance of learning, curiosity, discovery, and growth – for both coach and coachee.

References

Grant, A. M. (2011). Is it time to REGROW the GROW model? Issues related to teaching coaching session structures. The Coaching Psychologist, 7(2), 118–126.

Entwistle, N., & Tait, H. (1990). Approaches to learning, evaluations of teaching, and preferences for contrasting academic environments. Higher education, 19(2), 169-194.

ICF (nd) What is coaching? Accessed at: https://coachingfederation.org/

ICF (nd) ICF Core Competencies. Accessed at: https://coachingfederation.org/credentials-and-standards/core-competencies

Maltbia, T. E., Marsick, V. J., & Ghosh, R. (2014). Executive and organizational coaching: A review of insights drawn from literature to inform HRD practice. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 16(2), 161-183.

Mezirow, J. (1998). On critical reflection. Adult education quarterly, 48(3), 185-198.

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of transformative education, 1(1), 58-63.

Trigwell, K., Prosser, M. (1991). Relating approaches to study and quality of learning outcomes at the course level. British Journal of Education Psychology, 61, 265-275

Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of applied psychology, 98(2), 310.

Stanton, J. D., Sebesta, A. J., & Dunlosky, J. (2021). Fostering metacognition to support student learning and performance. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 20(2), fe3.

Webster-Wright, A. (2009). Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning. Review of educational research, 79(2), 702-739.