What is team coaching?

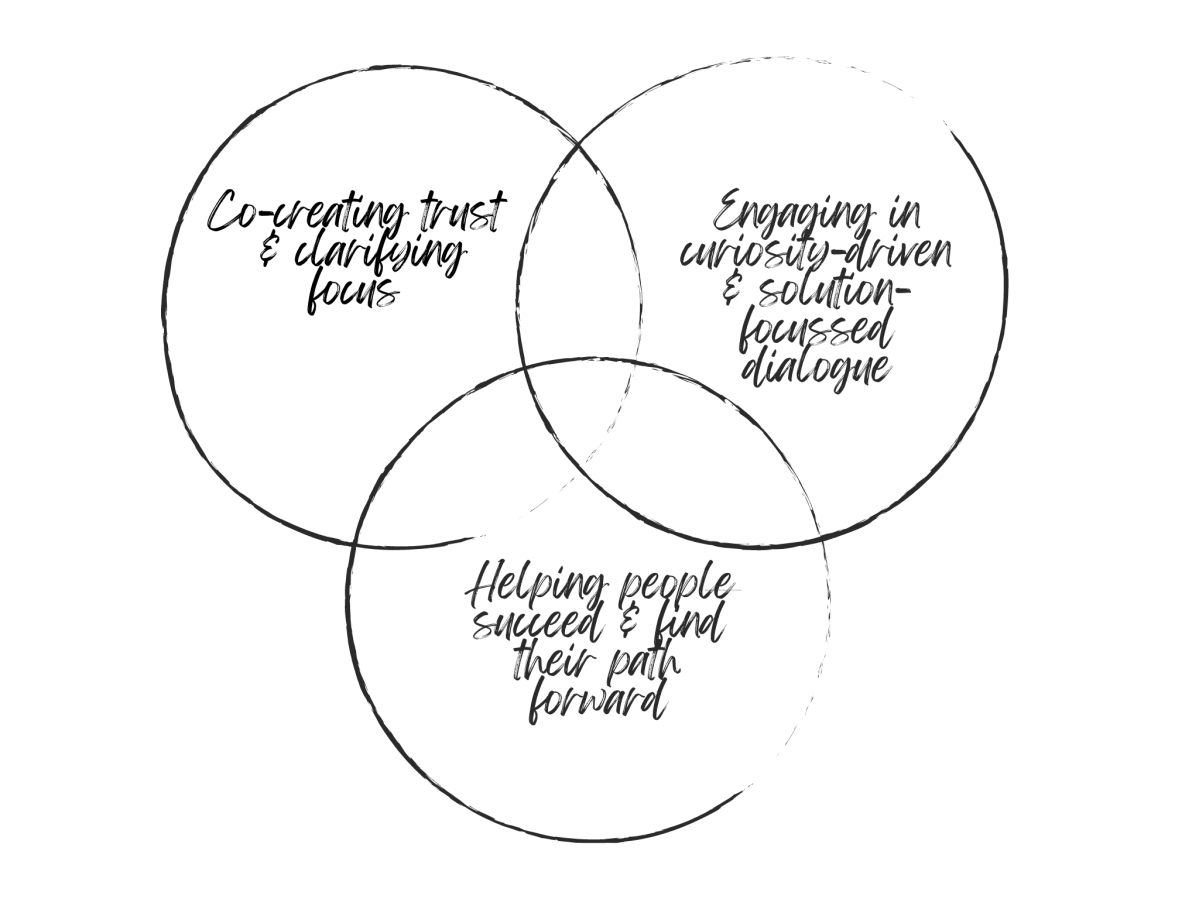

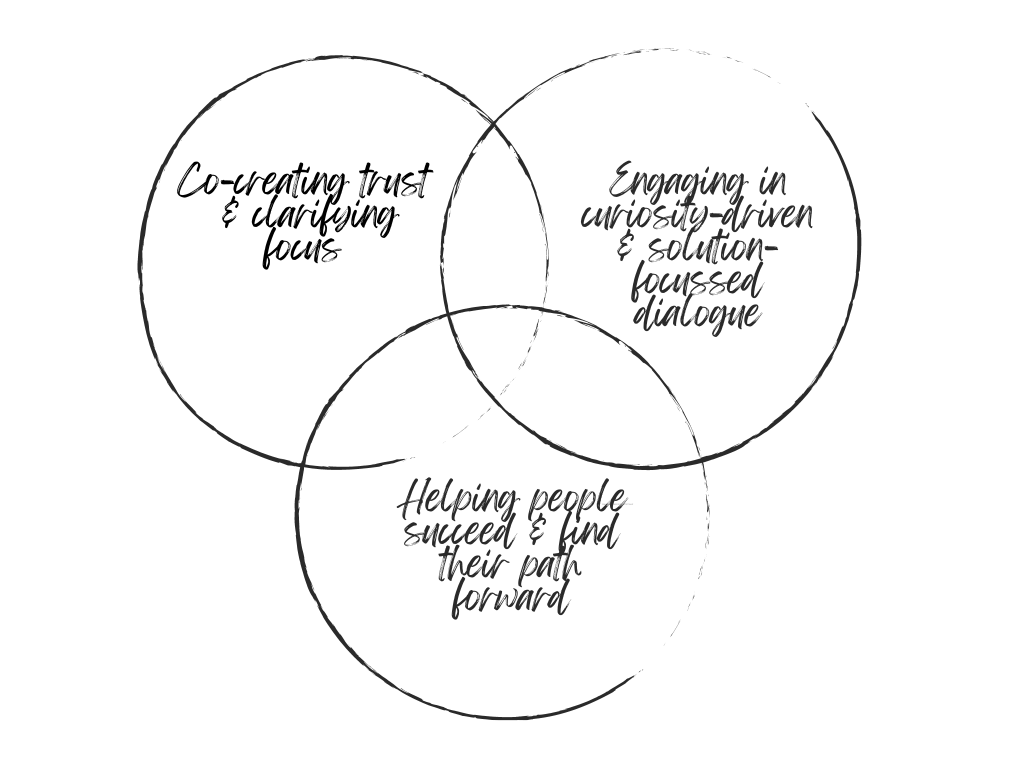

Team coaching involves partnering with and walking alongside teams to help them learn together, relate together, reflect together, achieve together, and grow together. Team coaching supports teams in leveraging their collective talents and gifts to achieve goals, strengthen performance, enhance team health, and transform themselves, their team and their organization(s). Traylor et al. (2020) summarize that team coaching focuses on learning and development, goals and performance, team self-awareness and team health/functioning over a sustained time. Team coaching is systemic and intentional, focusing on individual, interpersonal and team relationships; team priorities and tasks; internal and external partner connections; and, wider systemic/societal contexts (Lines and Leary-Joyce, 2024; Peters and Carr, 2013a). Team coaching positively impacts team performance, interaction, communication, affect (e.g., trust, respect, psychological safety), as well as ongoing team and individual learning and growth (Salihovic, 2021; Peters and Carr, 2013b).

What does team coaching look like?

Team coaching is nuanced and complex. Important approaches to team coaching include:

- using a combination of team coaching and individual coaching with team members and team leads,

- iteratively gathering insights from the team, organizational partners, and external partners,

- creating and maintaining conditions for psychological safety (Edmundson, 1999; 2018) and growth,

- challenging and stretching performance for individual team members and the team as a whole,

- providing expertise, mentorship, facilitation, and guidance where helpful,

- building conditions for sustained team health and change,

- evaluating and communicating the impact of team coaching interventions, and

- paying attention to our own growth, restoration and self-care (Graves, 2021).

According to Peters and Carr (2013a) the structure of team coaching includes six core components:

- Assessment (team coaching readiness, engagement of team members, stakeholders and context),

- Coaching for Team Design (team purpose, structure and talent),

- Team Launch (team charter, direction, vision, goals, working agreements),

- Individual Coaching (leader, team members),

- Ongoing Team Coaching (coach, team lead, team members, peer coaching), and

- Capturing Learning, Success and Impact (results and outputs, team and social processes, individual learning, partner perspectives).

The importance of psychological safety in team coaching

Psychological safety is core to team processes, especially when teams are navigating conflict. Gallo (2023) describes psychological safety as “a shared belief held by members of a team that it’s OK to take risks, to express their ideas and concerns, to speak up with questions, and to admit mistakes — all without fear of negative consequences.” Based on work by Amy Edmondson (e.g. Edmondson, 1999; Edmondson, 2018), Gallo emphasizes that psychological safety creates more motivated and engaged teams, leads to better decision-making, and fosters a culture of continuous improvement. In short, psychological safety leads to better team communication, performance, creativity, resilience, and learning.

What’s core to ensuring psychological safety?

Bresman and Edmondson (2022) highlight three key approaches leaders or coaches can take to create psychological safety:

- Framing: Frame team meetings and conversations as important opportunities for collaborative information sharing and intentionally invite team members to share different perspectives. Ensure you provide space and time to hear from all team members. Frame differences as valuable from the start.

I anticipate that we will all bring different perspectives to this conversation. Our diverse viewpoints will help us more fully understand each other and the issue at hand. These different perspectives enrich our discussion and help us arrive at a better outcome.

- Inquiry: This is what coaches do best! Ask open questions that inspire deep dialogue. Great leaders and coaches ask questions that are curious, learning-focused, and have no correct or pre-determined answer. Don’t know what to ask? Keep it simple.

What do you think?

What else might we consider?

How do you feel about this?

What matters most?

How should we move forward?

- Bridging Boundaries: I love this one. Bresman and Edmondson (2022) recommend that strength-based questions around hopes, skills and expertise, and challenges can help build psychological safety. These questions help team members see where they can bridge their expertise and boundaries. They provide a foundation for moving forward and stealthily inspire vulnerability.

What do you want to accomplish?

What do you bring to the table?

What are you up against? What are you worried about? What concerns you?

Digging deep to inspire team transformation

Team coaching is more than what you do or how you structure an experience with a team. Team coaching is coaching, and coaching is about transformation. It’s about digging below the surface.

Expert team coaches work to create psychologically safe spaces for open and honest conversations. They help teams lean into and resolve conflicts and disagreements. They learn to read the space by noticing shifts in energy, somatic responses and communication patterns to uncover what matters most. They are calm, affirming, and curious. They name shifts in team dynamics and are “prepared to drop the plan and respond to what is emerging in the team” (Lines and Leary-Joyce, 2024, p. 109).

This is the messy, magical, and essential part of team coaching that inspires new awareness and insight and results in sustained learning and transformation. It forms the heart of team coaching. This type of learning happens when teams uncover and challenge their assumptions, beliefs and frames of reference (Mezirow, 1997). Make no mistake, this is tough work. For coaches, this means leaning into team dynamics, team conflict, team tensions, team energy, team safety, team interaction, and the unspoken undercurrents of team processes.

Digging below the surface takes practice and courage. It often starts with listening to our inner wisdom. As coaches, our emotional responses and inner sensory reactions are powerful indicators that something is happening with the team that we need to pay attention to. Tuning into our inner wisdom is a coaching superpower, and mindfulness practices can help us develop this superpower.

Using the RAIN mindfulness practice to harness our inner wisdom and transform teams

I first learned about the RAIN mindfulness practice through Dr. Tara Brach’s work. I often use the RAIN (Brach, 2021) practice to navigate and live through the inevitable and common human experiences associated with stress, anxiety, anger, fear, frustration, grief, sadness, and burnout. RAIN stands for Recognize, Allow, Investigate, and Nuture.

Let’s break down how to leverage the RAIN practice to navigate tension and conflict in team coaching.

Imagine you are coaching a team, and you suddenly feel tension arising.

Drawing upon the work of Lines and Leary-Joyce’s (2024) approach to conflict and Brach’s (2021) RAIN framework, here is an example of how RAIN can help. Take note of how RAIN is used as an internal strategy for the team coach and as a coaching framework for the team throughout this example.

Recognize

Recognize what is happening and note what is emerging within you. Tap into your inner wisdom. Your feeling body is filled with wisdom. It has much to offer and teach your thinking mind. Pause and reflect on questions such as:

What thoughts, behaviours, and feelings am I experiencing?

What emotions are surfacing for me?

Where are these emotions living in my body?

What sensations am I experiencing?

What are these sensations wanting from me?

How could these feelings be an indicator of what others are feeling?

To help the team recognize and name what they are experiencing, identify what you are experiencing and invite them into the process.

I am feeling some tension arising. Do any of you feel that way, too?

Allow

Allow the experience, emotions, and sensations to be there, just as they are. There is no need to suppress, fix, judge or avoid these arisings. Remember that these reactions are there to support and help you. They are alerting you to pause and pay attention to something important. They are there to support your and the team’s success and learning.

You may acknowledge your sensations silently in a way that is meaningful to you.

I see you anxiety. I feel you as my jaw and hands clench.

To help the group uncover and allow their experiences, explore questions such as,

What are you noticing or experiencing as a team?

What emotions or sensations are you noticing arise within you?

Allowing is about creating space for folks to name, acknowledge and sit with their discomfort. Your role as team coach is to create a safe, open discussion where team members can identify what they are experiencing without judgment. It is the beginning of helping the team identify patterns of conflict and their impact on team dynamics and performance.

It may be helpful for team members to use statements starting with,

I feel…

I am…

I notice…

Create space for all voices to be heard. Encourage team members to name and sit with their discomfort, rather than judge, blame or rush to solutions. Validate and encourage different perspectives and encourage team members to do the same. Remember, this inner work is tough and may be new to many team members. Some team members may benefit from accessing an emotions or feelings wheel. I still use an emotions wheel regularly, as in the moment, it’s tough to identify what’s happening within us!

Your calm and reassuring presence is essential. Consider taking grounding breaths throughout the process. Affirming statements can help folks ease into the conversation.

It’s natural for strong emotions to arise during conflict.

Different people may experience this situation differently.

Investigate

Investigate with curiosity, interest and care. Investigation starts with you. You may silently reflect on questions such as,

What information are my emotional sensations providing me about my experiences as a team coach?

What information are these arising providing me about the team structure, dynamics and processes and the broader system they function within?

What patterns in the team’s dynamics and interactions am I noticing?

To dig deeper into an exploration of tension and conflict with the team, you may explore questions such as,

What patterns are you noticing?

What is this situation offering or teaching the team? What opportunities is it revealing?

How might the team structure be contributing to this situation?

What broader organizational dynamics or external contexts may be contributing to this situation?

What are your roles, contributions and responsibilities related to this situation?

What strengths could emerge from working through this?

What do you need from the team in this moment?

What does the team need from you?

Again, your calming and curious presence is essential. Notice your and the team’s tone, posture and somatic responses and intentionally work to ease tension throughout the discussion. Take pauses and breaks if necessary.

Nurture

Nurture psychological safety and demonstrate compassion and self-compassion. Demonstrate compassion and encourage self-compassion by openly acknowledging, appreciating and affirming courageous and vulnerable contributions.

Self-compassion (Neff, 2023) involves giving ourselves support and compassion, just as we would a friend, especially when we are experiencing discomfort, suffering and pain. It includes demonstrating self-kindness, acknowledging the common humanity of our experiences, and practicing mindfulness. It is about reducing the separation we feel from one another.

Working through conflict and disagreement is tough work. Self-compassion can be demonstrated throughout the RAIN cycle. For example, you may silently acknowledge,

Working through conflict is an important component of my role as coach. It’s tough work.

The gentle movement of placing one of your hands on top of the other can help demonstrate self-compassion and care.

Encourage self-compassion and compassion by the team by normalizing and emphasizing the importance of team conflict.

Thank you for working through this process. Conflict and disagreement are critical to fostering team health.

Working through moments of tension, conflict and disagreement provide incredible opportunities for team learning, innovation, and growth.

It takes courage, expertise and vulnerability to lean into team tensions. You’ve strengthened the way you interact as a team and surfaced new and different perspectives.

Nurture psychological safety through shared framing, inquiry and bridging boundaries (Bresman and Edmundson, 2022). Check-in and facilitate a debrief to synthesize what the team learned and how they will move forward. Ensure you allow for time to hear from all team members.

The act of psychological safety is a demonstration of compassion and self-compassion as the team is provided with time to normalize and mindfully reflect upon the learning and growth they have accomplished.

Consider questions such as,

What strengths emerged from working through this?

What did you learn about navigating team conflict and ensuring psychological safety as you worked through this? As individuals? As a team?

How will you carry forward what you learned as a team?

What might you add to your team agreements based on this experience?

How will you reflect upon and celebrate the work and growth you have experienced today?

Conclusion

Listening to and leaning into our inner wisdom is one of the most important practices we can develop as team coaches. Like any practice, it takes practice! RAIN provides an accessible framework for helping us leverage our and the team’s inner wisdom to navigate tension, disagreement and conflict, and to strengthen psychological safety.

RAIN has completely reframed conflict and tension for me. It’s helped me see this discomfort as an essential part of team health, learning and growth. Most importantly, it’s given me a grounded approach to strengthen my capacity to help team members and teams become more curious, human-centred and resilient.

Call to action

I encourage you to find one component of the RAIN practice that resonates with you and to try it in a team coaching experience. The RAIN practice can apply to your individual leadership and coaching practices too. You may start by recognizing the emotions and sensations that arise within you during a team discussion, or by engaging in a conversation of what the team experiences during a moment of energy, passion and joy. RAIN can also illuminate joyful team experiences. You may start by sharing and discussing this post with a coaching colleague or a leadership team you are working with. There is no one or right way to bring the RAIN practice to life. Do what feels most meaningful and important to you!

References

Brach, T. (2021) Blog: The RAIN of self-compassion. https://www.tarabrach.com/selfcompassion1/

Bresman, H. and Edmondson, A. (2022) Research: to excel, diverse teams need psychological safety. https://hbr.org/2022/03/research-to-excel-diverse-teams-need-psychological-safety

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons.

Gallo, A. (2023) What is psychological safety? https://hbr.org/2023/02/what-is-psychological-safety

Graves, G. (2021). What do the experiences of team coaches tell us about the essential elements of team coaching? International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 15. https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/file/fe000ae4-258d-4fed-8fcb-8d2d484295e1/1/IJEBCM_S15_16.pdf

Lines, H. and Leary-Joyce, J. 2024. Systemic Team Coaching 2nd Edition. AoEC Press.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New directions for adult and continuing education, 1997(74), 5-12. https://www.ecolas.eu/eng/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Mezirow-Transformative-Learning.pdf

Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual review of psychology, 74(1), 193-218.

Peters, J., & Carr, C. (2013a). High Performance Team Coaching: A Comprehensive System for Leaders and Coaches. Friesen Press.

Peters, J., & Carr, C. (2013b). Team effectiveness and team coaching literature review. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 6(2), 116-136. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17521882.2013.798669

Salihovic, K. (2021). Team coaching in the workplace. A literature review on team coaching and solving performance deficiency in the workplace, University of Gothenburg, School of Business, Economics and Law.

Traylor, A. M., Stahr, E., & Salas, E. (2020). Team coaching: Three questions and a look ahead: A systematic literature review. International Coaching Psychology Review, 15(2), 54-68. https://www.siopsa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ICPR-Vol-15.-No.-2-Autumn-2020.pdf#page=56